In everyday life, “permanent magnets” are often thought to possess unlimited magnetic strength. From a strict physics perspective, however, magnetism is not absolutely eternal. Although high-quality magnets can retain their magnetic strength for decades or even centuries under ideal conditions, various environmental factors can gradually weaken the alignment of their magnetic domains.

The Scientific Principle Behind Magnetic Loss: Demagnetization

A magnet produces a magnetic field because its internal “magnetic domains” are aligned in the same direction. When this alignment is disturbed and becomes disordered, the magnet undergoes “demagnetization.”

Although natural decay is extremely slow, the following four key factors are the primary causes of premature magnetic “failure”:

1. Temperature Effects (Thermal Demagnetization)

Heat is a magnet’s greatest enemy. Every magnetic material has a specific maximum operating temperature and a Curie temperature.

Curie Temperature:

When a magnet is heated to this specific temperature, intense atomic vibrations cause the magnetic domains to become completely disordered, resulting in a total loss of magnetism.

Operating Temperature:

Before reaching the Curie temperature, exceeding the recommended operating temperature can cause reversible or irreversible loss of magnetic strength. For example, ordinary neodymium magnets begin to show noticeable magnetic decline when temperatures exceed 80 °C.

2. Mechanical Impact and Physical Damage

Strong impacts, drops, or vibrations can disrupt domain alignment through physical energy. For brittle materials such as ferrite or neodymium magnets, physical damage not only reduces the magnet’s volume but also lowers magnetic flux due to changes in internal stress.

3. External Opposing Magnetic Fields

If a magnet is exposed to a strong opposing magnetic field, such as being placed near a stronger magnet or a powerful electromagnetic field, the internal magnetic pole directions may be forcibly twisted or neutralized, leading to demagnetization.

4. Chemical Corrosion and Oxidation

The chemical stability of a magnet determines its durability.

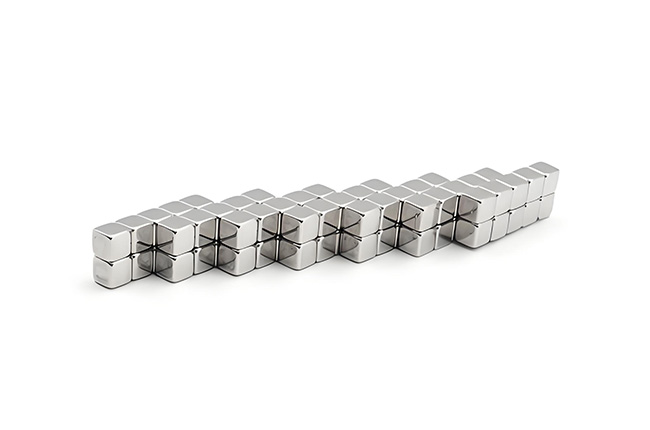

Neodymium Magnets (NdFeB):

Containing a large amount of iron, they are highly prone to oxidation and rust. Once corrosion occurs, the magnet begins to flake from the surface, causing rapid degradation of magnetic performance. This is why most strong magnets are coated with nickel or epoxy resin.

Samarium Cobalt Magnets and Ferrite Magnets:

These have excellent corrosion resistance and usually do not require protective coatings.

Expected Lifespan of Different Types of Magnets

The rate of demagnetization varies significantly depending on the material. Under ideal conditions without extreme heat or strong interference, their performance is as follows:

Neodymium Magnets:

Currently the strongest commercially available magnets, neodymium magnets are highly stable. At room temperature, they lose only about 1% of their magnetic strength every 100 years. With proper protection, their service life can easily exceed that of a human lifespan.

Samarium Cobalt Magnets:

Designed for extreme environments, these magnets are not only corrosion-resistant but can also operate at temperatures up to 300 °C. Their magnetic stability is extremely high, with virtually no noticeable degradation over time.

Ferrite (Ceramic) Magnets:

Although their magnetic strength is weaker, ferrite magnets have excellent chemical stability and strong resistance to demagnetization. As long as there is no severe physical damage, their performance changes very little over several decades.

Alnico Magnets:

While these magnets are resistant to high temperatures, they are highly susceptible to demagnetization from external magnetic fields. If mistakenly stored near stronger magnets, they may lose their magnetism in a short period of time.

How to Extend the Service Life of Magnets

To ensure magnets perform effectively for as long as possible, the following storage and usage guidelines are recommended:

Temperature Control: Use magnets below their rated operating temperature and keep them away from heat sources.

Moisture and Rust Prevention: For neodymium magnets, ensure a dry storage environment. If the coating is damaged, repair or replace the magnet promptly.

Proper Storage: Use magnetic keepers to close the magnetic circuit during storage. When storing multiple magnets, keep them in an attracting configuration rather than a repelling one.

Avoid Electromagnetic Interference: Do not place magnets near high-power electrical equipment or transformers for extended periods.

Conclusion

In normal industrial or household applications, high-quality permanent magnets can generally be considered “lifetime-effective.” Although from a physics standpoint they may lose less than 1% of their magnetic flux per century, this change is practically negligible in real-world use. What truly shortens a magnet’s lifespan is not time, but improper temperature control and inadequate physical protection.

Contact

We will contact you within 24 hours. ( WhatsApp/facebook:+86 15957855637)